Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Liver Cancer > Volume 23(2); 2023 > Article

-

Original Article

The efficacy of treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients -

Han Ah Lee1*

, Sangheun Lee2*

, Sangheun Lee2* , Hae Lim Lee3

, Hae Lim Lee3 , Jeong Eun Song4

, Jeong Eun Song4 , Dong Hyeon Lee5

, Dong Hyeon Lee5 , Sojung Han6

, Sojung Han6 , Ju Hyun Shim7

, Ju Hyun Shim7 , Bo Hyun Kim8

, Bo Hyun Kim8 , Jong Young Choi9

, Jong Young Choi9 , Hyunchul Rhim10

, Hyunchul Rhim10 , Do Young Kim11,12

, Do Young Kim11,12

-

Journal of Liver Cancer 2023;23(2):362-376.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17998/jlc.2023.08.03

Published online: September 14, 2023

1Department of Internal Medicine, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

2Department of Internal Medicine, Catholic Kwandong University International St. Mary's Hospital, Catholic Kwandong University College of Medicine, Incheon, Korea

3Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

4Department of Internal Medicine, Daegu Catholic University School of Medicine, Daegu, Korea

5Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, SMG-SNU Boramae Medical Center, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

6Department of Internal Medicine, Uijeongbu Eulji Medical Center, Eulji University, Eulji University School of Medicine, Uijeongbu, Korea

7Department of Gastroenterology, Liver Center, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

8Center for Liver and Pancreatobiliary Cancer, National Cancer Center, Goyang, Korea

9The Catholic University Liver Research Center, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

10Department of Radiology, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

11Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

12Yonsei Liver Cancer Center, Severance Hospital, Seoul, Korea

-

Corresponding author: Do Young Kim, Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, 50-1 Yonsei-ro, Seodaemun-gu, Seoul 03722, Korea

Tel. +82-2-2228-1992, Fax. +82-2-393-6884 E-mail: dyk1025@yuhs.ac - *Han Ah Lee and Sangheun Lee contributed equally to this work as co-first authors.

© 2023 The Korean Liver Cancer Association.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 1,735 Views

- 87 Downloads

- 2 Citations

Abstract

-

Background/Aim

- Despite the increasing proportion of elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) over time, treatment efficacy in this population is not well established.

-

Methods

- Data collected from the Korean Primary Liver Cancer Registry, a representative cohort of patients newly diagnosed with HCC in Korea between 2008 and 2017, were analyzed. Overall survival (OS) according to tumor stage and treatment modality was compared between elderly and non-elderly patients with HCC.

-

Results

- Among 15,186 study patients, 5,829 (38.4%) were elderly. A larger proportion of elderly patients did not receive any treatment for HCC than non-elderly patients (25.2% vs. 16.7%). However, OS was significantly better in elderly patients who received treatment compared to those who did not (median, 38.6 vs. 22.3 months; P<0.001). In early-stage HCC, surgery yielded significantly lower OS in elderly patients compared to non-elderly patients (median, 97.4 vs. 138.0 months; P<0.001), however, local ablation (median, 82.2 vs. 105.5 months) and transarterial therapy (median, 42.6 vs. 56.9 months) each provided comparable OS between the two groups after inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) analysis (all P>0.05). After IPTW, in intermediate-stage HCC, surgery (median, 66.0 vs. 90.3 months) and transarterial therapy (median, 36.5 vs. 37.2 months), and in advanced-stage HCC, transarterial (median, 25.3 vs. 26.3 months) and systemic therapy (median, 25.3 vs. 26.3 months) yielded comparable OS between the elderly and non-elderly HCC patients (all P>0.05).

-

Conclusions

- Personalized treatments tailored to individual patients can improve the prognosis of elderly patients with HCC to a level comparable to that of non-elderly patients.

- Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most prevalent cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in Korea.1,2 A substantial proportion of patients diagnosed with HCC are elderly, and older age is recognized as a significant risk factor for development of HCC.3 Over the past few decades, advances in the treatment of chronic liver diseases have resulted in increased life expectancy, resulting in growing number of elderly patients affected by HCC.4 Furthermore, the elderly population in Korea exceeded 14% in 2018, contributing to the increasing disease burden among this age group of HCC patients.5

- Currently, the progression of viral hepatitis has been delayed by the development of antiviral drugs, resulting in a decrease in the incidence of HCC in Asia, particularly in regions with a high prevalence of chronic hepatitis B.6 However, despite an overall decrease in the incidence of total HCC in South Korea from 2008 to 2018, there has been a continued increase in the age-standardized incidence of HCC among elderly individuals.7 Projections indicate that the crude incidence of HCC in the elderly is expected to increase, accounting for 21.3% of the total HCC population by 2028. This increasing incidence in the elderly population can be partly attributed to the limitations of current antiviral agents, which still carry the risk of developing HCC during long-term treatment.8

- Despite the significant increase in the disease burden of HCC among elderly individuals, there remains considerable controversy regarding the appropriate treatment options for managing this patient population.9 One of the primary factors contributing to this controversy is the lack of representation of elderly patients in clinical trials, which has led to undertreatment for this group.9 Concerns related to co-existing comorbidities, fragility, and decreased liver function further complicate treatment decisions. However, several studies investigating the feasibility and safety of various therapeutic approaches in elderly patients with HCC have shown that advanced age is not a contraindication for treatment. These findings highlight the need for an active treatment approach for elderly patients with HCC. A recent study reported that elderly patients who received active treatment had a higher overall survival (OS) rate than those who did not.10

- In this study, we aimed to investigate the efficacy and safety of HCC treatment in elderly patients, focusing specifically on different tumor stages. We used data from the Korean Primary Liver Cancer Registry (KPLCR), a comprehensive and representative database of patients newly diagnosed with primary liver cancer in Korea.

INTRODUCTION

- 1. Patients

- Patients with HCC registered in the KPLCR between January 2008 and December 2017 were screened. The KPLCR is a representative sample of patients with newly diagnosed primary liver cancer that was randomly extracted from the Korean Central Cancer Registry (KCCR), which registers more than 95% of all cancer cases in Korea. Approximately 15% of the patients with newly diagnosed primary liver cancer in the KCCR were selected for inclusion in the KPLCR after stratification based on region and hospital.

- The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age <18 years, (2) patients who received their initial treatment more than 120 days after the date of diagnosis, (3) patients lacking information on the treatment modality, (4) insufficient followup period (<6 months), and (5) insufficient clinical or laboratory information (Supplementary Fig. 1). The requirement for written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this study. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Ewha Womans University Hospital waived the need for IRB approval and written informed consent (IRB No. 2023-02-028) because the KPLCR data were collected anonymously as part of the KCCR in accordance with the cancer control act. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines were followed (Supplementary Table 1).

- 2. Data collection and definitions

- Elderly was defined as individuals who are 65 years of age or older. HCC was diagnosed based on histological evidence or dynamic computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings (nodule >1 cm with arterial hypervascularity and portal/delayed-phase washout).11

- Patient data were collected from the medical records at each hospital where the HCC diagnosis was made. Trained data recorders from the KCCR affiliated with each hospital examined the medical records. These data recorders, who were well trained and experienced in handling cancer registry data, followed standardized procedures for data extraction. They used a standardized case record form specifically designed for this study to ensure consistency and uniformity of the data collection. To maintain data quality and accuracy, the extracted data were further validated by statisticians affiliated with both the KCCR and KPLCR. These statisticians reviewed the collected data, conducted quality checks, and ensured data reliability.

- The collected data included baseline characteristics such as demographic information, laboratory results, tumor variables, and treatment-related factors such as treatment methods and patient OS. Diagnostic imaging techniques such as dynamic CT or MRI scans were employed to assess tumor characteristics. The modified Union for International Cancer Control (mUICC) and Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging systems were used for staging. OS was measured from the date of HCC diagnosis to death from any cause. Information from death certificates was acquired from the national statistical data collected by the Korean Ministry of Government Administration and the Ministry of Home Affairs. To ensure the identification and tracking of individual patients throughout the study, a distinct 13-digit resident registration number assigned to all Koreans was used for each patient. Data collection was completed on December 31, 2020, the data cut-off date.

- 3. Statistical analysis

- Data are presented as either numbers with percentages or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), depending on the nature of the variables. The statistical significance of the differences between continuous and categorical variables was assessed using either a student's t-test or Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables and a chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. The OS of the patients was assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences in survival between the groups were compared using the log-rank test.

- Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was employed to correct for selection bias, and the propensity score was calculated using binary logistic regression. In addition, propensity score matching (PSM) was conducted independently in both cohorts to ensure reproducibility of the results. For PSM, a nearest-neighbor 1:1 matching method with a caliper size of 0.1 was used. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 21.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Two-sided P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

METHODS

- 1. Baseline characteristics of elderly and non-elderly patients

- Table 1 provides an overview of the baseline characteristics of the elderly and non-elderly patients. The median age of the elderly patients was 72.0 years, and that of the non-elderly patients was 54.0 years (P<0.001). When comparing comorbidities, a higher proportion of the elderly patients had diabetes (34.8% vs. 21.0%) and hypertension (52.4% vs. 23.8%) than non-elderly patients (all P<0.001). Elderly patients had a lower prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection (33.8% vs. 75.8%) but a higher prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection (17.7% vs. 5.7%), alcoholic liver disease (18.1% vs. 8.7%), and other liver diseases (30.4% vs. 9.8%) than non-elderly patients (P<0.001). The median model for end-stage liver disease score was significantly higher in elderly patients than in non-elderly patients (9.0 vs. 8.0; P=0.015).

- Among elderly patients, a single tumor was observed in 62.0% of cases, while among non-elderly patients, it was observed in 61.0% of cases. The median maximal tumor diameter was larger in elderly patients than in non-elderly patients, measuring 3.5 and 3.0 cm, respectively (P<0.001). Using the mUICC staging system, stages I, II, III, IV-A, and IV-B accounted for 13.4%, 40.0%, 28.0%, 9.9%, and 8.7%, respectively, of elderly patients, and 16.1%, 35.9%, 24.0%, 13.1%, and 10.9% of non-elderly patients, respectively. According to the BCLC staging system, stages 0, A, B, C, and D accounted for 10.0%, 39.2%, 14.2%, 15.6%, and 16.0% respectively, of elderly patients and 11.7%, 35.5%, 10.8%, 19.2%, and 17.2% of non-elderly patients, respectively.

- 2. Change in the proportion of elderly patients

- The proportion of elderly patients among all included patients has been increasing gradually. The specific percentages are 33.5% in 2008, 33.8% in 2009, 35.9% in 2010, 34.5% in 2011, 37.4% in 2012 and 2013, 40.0% in 2014, 40.7% in 2015, 44.9% in 2016, and 45.9% in 2017 (Fig. 1).

- 3. Initial treatment modality in elderly and non-elderly patients

- Table 2 presents the initial treatment modalities for the elderly and non-elderly patients. A higher proportion of patients in the elderly group did not receive any treatment after the diagnosis of HCC than those in the non-elderly group (25.2% vs. 16.7%). In early-stage HCC (BCLC stage 0 or A), a lower proportion of patients in the elderly group received surgical treatments, including resection and liver transplantation, than in the non-elderly group (23.9% vs. 39.5%). In contrast, a higher proportion of patients in the elderly group received transarterial therapy than in the non-elderly group (45.0% vs. 36.3%). Local ablation therapy was performed in 19.2% of elderly and 19.0% of non-elderly patients. Among patients with intermediate-stage HCC (BCLC stage B), the proportion receiving transarterial therapy was 63.0% in the elderly and 63.8% in the non-elderly patients. A lower proportion of elderly patients received surgical treatment than non-elderly patients (11.6% vs. 17.7%). In advanced-stage HCC (BCLC stage C), a lower proportion of patients in the elderly group received transarterial (34.9% vs. 42.9%) or systemic therapy (16.5% vs. 21.2%) than in the non-elderly group.

- 4. Overall survival

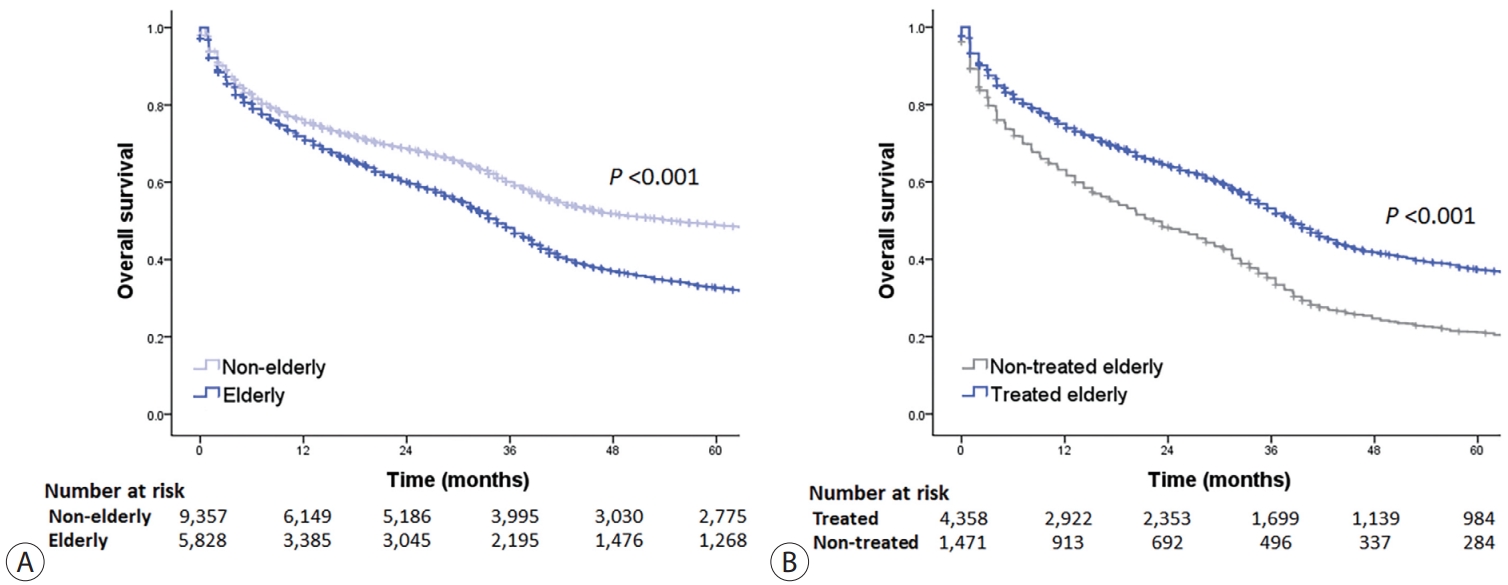

- The median OS was significantly shorter in elderly patients compared to non-elderly patients with a median OS of 34.5 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 33.4-35.6) in the elderly group and 54.8 months (95% CI, 50.7-58.9) in the non-elderly group (log-rank test, P<0.001) (Fig. 2A). The 1-, 3-, 5-year OS rates were 71.2%, 48.2%, and 32.7%, respectively, in elderly patients and 76.2%, 60.0%, and 48.9%, respectively, in non-elderly patients. The median OS was significantly longer in elderly patients who received any HCC treatment compared to those who did not, with a median OS of 38.6 months (95% CI, 37.3-39.9) in the treated group and 22.3 months (95% CI, 19.7-24.9) in the untreated group (log-rank test, P<0.001) (Fig. 2B). OS rates according to HCC stages and treatment modalities are presented in Table 3.

- In patients with early-stage HCC (BCLC stage 0 or A), the median OS was significantly shorter in elderly patients compared to non-elderly patients (41.6 months [95% CI, 38.9-44.3] vs. 111.6 months [95% CI, 106.6-116.6]; log-rank test, P<0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 2). The median OS was significantly longer in elderly patients who received any HCC treatment compared to those who did not, with a median OS of 44.7 months (95% CI, 40.8-48.6) in the treated group and 21.3 months (95% CI, 13.8-28.8) in the untreated group (log-rank test, P<0.001).

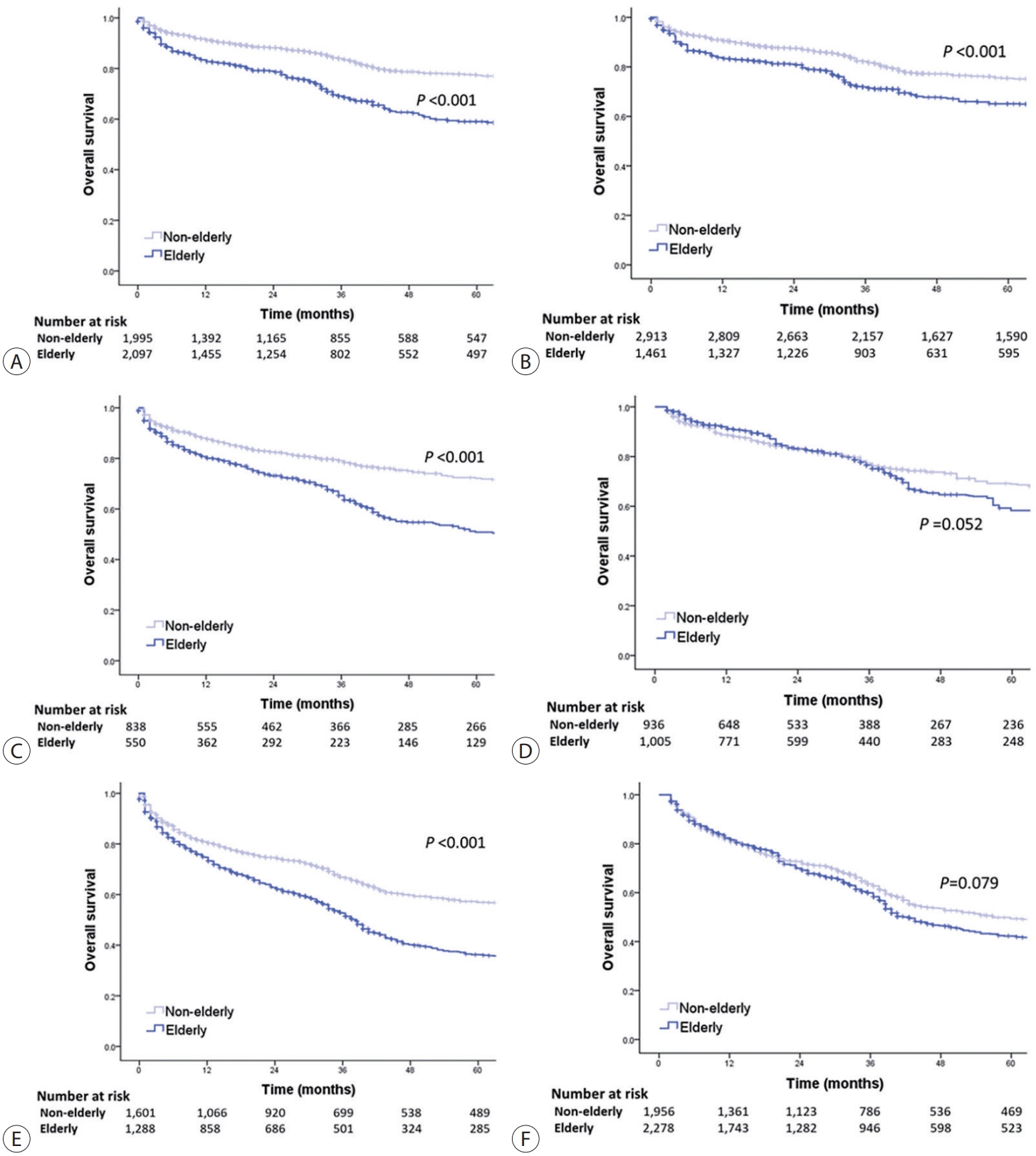

- The OS of elderly and non-elderly patients with early-stage HCC was compared based on treatment modality. In patients who underwent surgery, the median OS was significantly shorter in elderly patients compared to non-elderly patients (86.3 months [95% CI, 77.0-95.6] vs. 133.9 months [95% CI, 127.7-140.1]; log-rank test, P<0.001) (Fig. 3A). Similar results were obtained between the elderly and non-elderly groups after IPTW analysis (median OS, 97.4 months [95% CI, 92.0-102.8] vs. 138.0 months [95% CI, 126.1-141.7]; log-rank test, P<0.001) (Fig. 3B).

- In patients who recieved local ablation therapy, the median OS was significantly shorter in elderly patients compared to non-elderly patients (65.9 months [95% CI, 50.4-81.4] vs. 127.8 months [95% CI, 120.9-134.7]; log-rank test, P<0.001) (Fig. 3C). However, after performing IPTW analysis, the median OS of elderly patients was found to be comparable to that of non-elderly patients. (median OS, 82.2 months [95% CI, 74.7-89.7] vs. 105.5 months [95% CI, 99.1-111.9]; log-rank test, P=0.052) (Fig. 3D).

- Finally, in patients who received transarterial therapy, the median OS was significantly shorter in elderly patients compared to non-elderly patients (38.5 months [95% CI, 36.3-40.7] vs. 85.2 months [95% CI, 78.8-91.6]; log-rank test, P<0.001) (Fig. 3E). However, after performing IPTW analysis, elderly patients had comparable median OS to that of non-elderly patients (median OS, 42.6 months [95% CI, 39.6-45.6] vs. 56.9 months [95% CI, 47.6-66.2]; log-rank test, P=0.079) (Fig. 3F).

- In patients with intermediate-stage HCC (BCLC stage B), the median OS was significantly shorter in elderly patients compared with non-elderly patients (34.5 months [95% CI, 30.8-38.2] vs. 49.7 months [95% CI, 40.4-59.0]; log-rank test, P<0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 3). The median OS was significantly longer in elderly patients who received any HCC treatment compared to those who did not, with a median OS of 36.5 months (95% CI, 32.2-40.8) in the treated group and 28.4 months (95% CI, 20.1-36.7) in the untreated group (log-rank test, P<0.001)

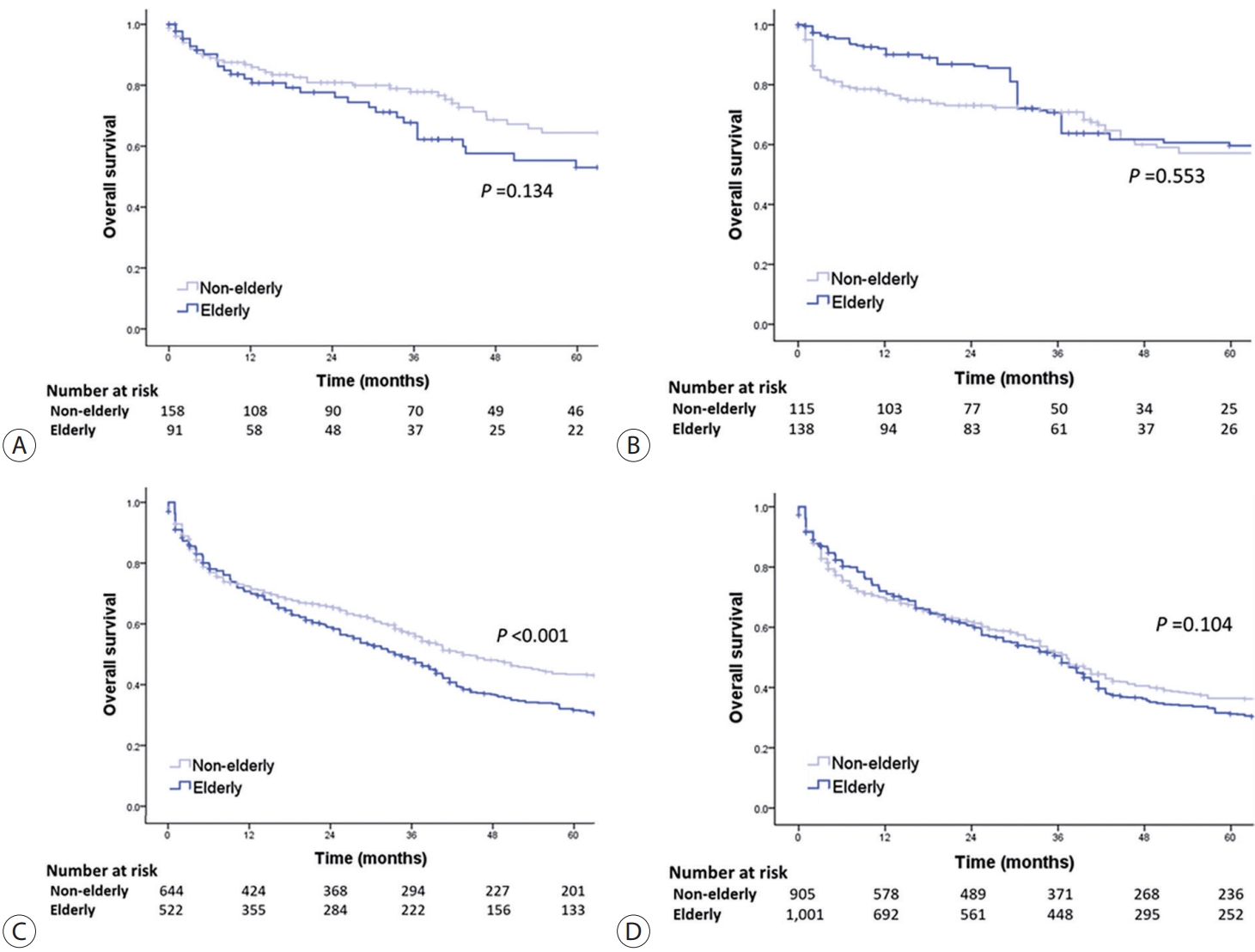

- The OS of elderly and non-elderly patients with intermediate-stage HCC was compared according to treatment modality. In patients treated with surgery, the median OS was comparable between the elderly and non-elderly groups (78.1 months [95% CI, 42.5-113.7] vs. 94.3 months [95% CI, 79.9-108.7]; log-rank test, P=0.134) (Fig. 4A). Similar results were observed between the elderly and non-elderly groups after conducting IPTW analysis (median OS, 66.0 months [95% CI, 52.1-79.9] vs. 90.3 months [95% CI, 74.2-106.4]; log-rank test, P=0.553) (Fig. 4B).

- In patients treated with transarterial therapy, the median OS was significantly shorter in elderly patients compared with non-elderly patients (33.5 months [95% CI, 28.5-38.5] vs. 43.6 months [95% CI, 36.9-50.3], log-rank test, P<0.001) (Fig. 4C). However, after conducting IPTW analysis, it was observed that elderly patients had a comparable median OS to that of non-elderly patients (median OS, 36.5 months [95% CI, 33.7-39.3] vs. 37.2 months [95% CI, 34.6-39.8], log-rank test, P=0.104) (Fig. 4D).

- In patients with advanced-stage HCC (BCLC stage C), the median OS was significantly shorter in elderly patients compared to non-elderly patients (24.3 months [95% CI, 21.1-27.5] vs. 31.4 months [95% CI, 29.0-33.8]; log-rank test, P<0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 4).The median OS was significantly longer in elderly patients who received any HCC treatment compared to those who did not, with a median OS of 31.4 months (95% CI, 29.4-33.4) in the treated group and 22.3 months (95% CI, 18.7-25.9) in the untreated group (log-rank test, P<0.001)

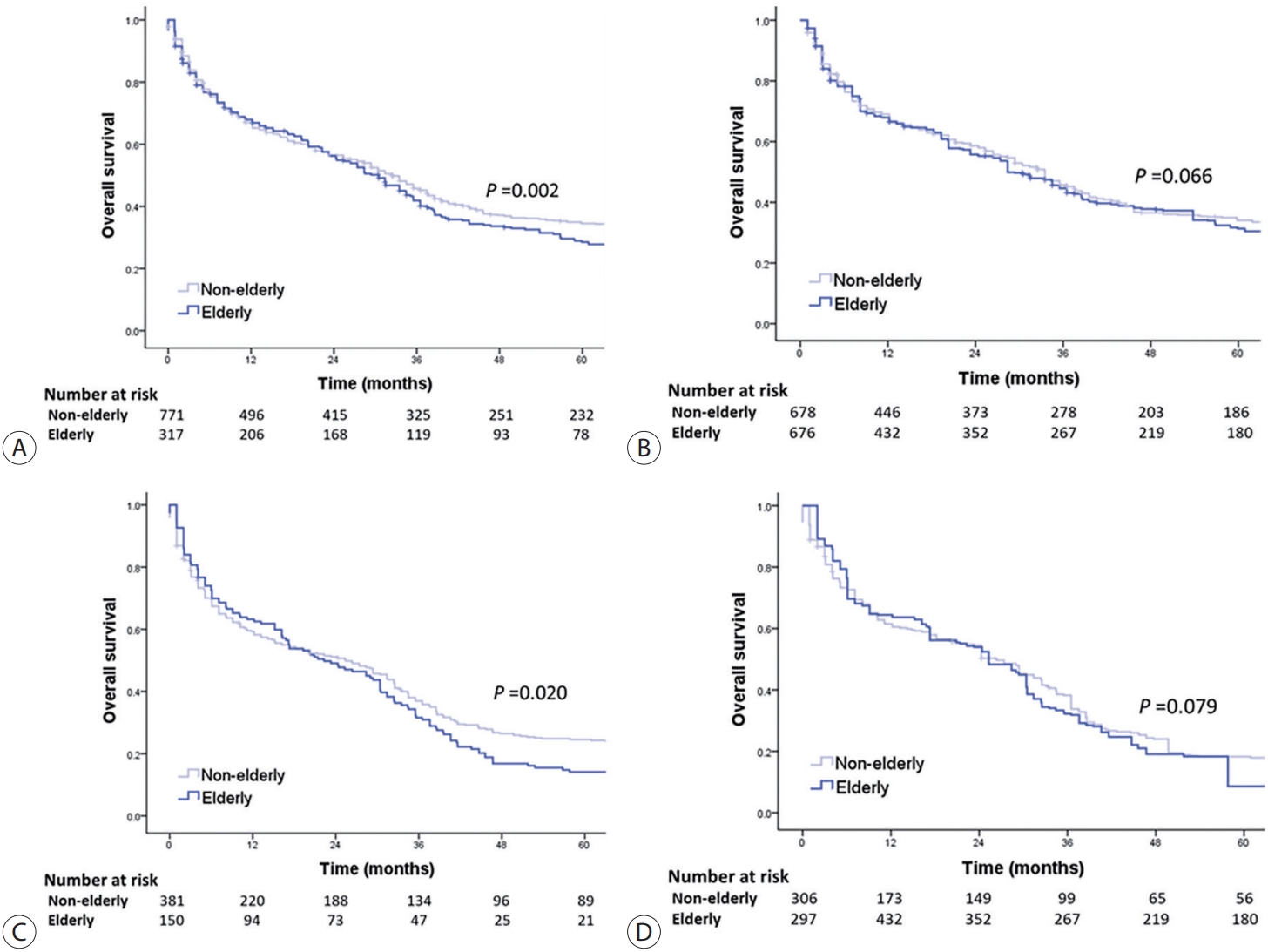

- The OS of elderly and non-elderly patients with advanced-stage HCC was compared according to treatment modality. In patients treated with transarterial therapy, the median OS was significantly shorter in elderly patients compared to non-elderly patients (30.5 months [95% CI, 25.3-35.7] vs. 32.5 months [95% CI, 28.8-36.2]; log-rank test, P=0.002) (Fig. 5A). However, after performing IPTW analysis, it was observed that elderly patients had a comparable median OS to non-elderly patients (median OS, 28.4 months [95% CI, 24.4-32.4] vs. 33.5 months [95% CI, 30.0-37.1]; log-rank test, P=0.066) (Fig. 5B).

- In patients treated with systemic therapy, the median OS was significantly shorter in elderly patients compared to non-elderly patients (22.3 months [95% CI, 13.5-31.1] vs. 25.4 months [95% CI, 18.3-32.5]; log-rank test, P=0.020) (Fig. 5C). However, after conducting IPTW analysis, elderly patients had comparable median OS to non-elderly patients (median OS, 25.3 months [95% CI, 20.6-30.0] vs. 26.3 months [95% CI, 21.4-31.2]; log-rank test, P=0.079) (Fig. 5D).

RESULTS

1) Early-stage HCC

2) Intermediate-stage HCC

3) Advanced-stage HCC

- The increasing number of elderly patients with HCC in Korea presents a significant socioeconomic challenge in terms of treatment. In the analysis of data from the KPLCR, it was found that elderly individuals accounted for 38.4% of newly diagnosed patients with HCC between 2008 and 2017. Notably, a larger proportion of elderly patients with HCC did not receive any treatment compared with the non-elderly group. However, it is important to highlight that among elderly patients who received treatment, there was a significant improvement in OS compared to those who did not. Furthermore, the analysis indicated that for most stages of HCC and treatment modalities, elderly patients had a comparable OS to non-elderly patients, except for early-stage HCC treated with surgery. These findings highlight the potential benefits of treatment in improving survival outcomes in elderly patients with HCC.

- Along with the growing elderly population, there was also an observed increase in the proportion of elderly patients with HCC in this study from 33.5% in 2008 to 45.9% in 2017. Elderly patients with HCC exhibit distinct characteristics compared to their non-elderly counterparts. A larger proportion of elderly patients with HCC in this study had comorbidities, such as diabetes and hypertension. In contrast to non-elderly patients with HCC, among whom HBV infection is the primary cause of HCC, non-HBV-related HCC is more prevalent in the elderly patient population. Hepatitis B is mainly transmitted vertically during childbirth; therefore, it typically affects young individuals. In contrast, hepatitis C usually develops after adulthood. Therefore, HBV-related HCC occurs approximately 10 years earlier than hepatitis C virus-related HCC.12 Among elderly HCC patients, the most prevalent cause of HCC is non-viral hepatitis, with a significant proportion likely attributed to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Due to the higher prevalence of metabolic disorders such as diabetes among elderly patients, there is a suspicion that NAFLD plays a significant role in the development of HCC in this population. This highlights the importance of careful recognition and management of NAFLD in elderly patients to prevent progression to HCC.

- Interestingly, a higher proportion of newly diagnosed elderly patients with HCC (approximately 25%) did not receive any treatment for HCC compared to non-elderly patients. Furthermore, elderly patients with HCC were treated with less invasive treatments than non-elderly patients. Transarterial therapy is the most commonly used treatment modality for early- and intermediate-stage HCC in the elderly population. In contrast, a higher proportion of advanced-stage elderly patients received the best supportive care, indicating a potentially more conservative treatment approach in this age group. This passive treatment approach observed in elderly patients with HCC may stem from general concerns regarding their prognosis compared to non-elderly patients, even when receiving the same treatment under similar circumstances. In addition, there are concerns regarding the potential for increased rates of side effects in the elderly population who have a higher incidence of comorbidities. However, these concerns can become a barrier to elderly patients with HCC receiving appropriate treatment and may result in missed treatment opportunities. It is important to note that among elderly patients with HCC, those who received HCC treatment had better survival outcomes than those who did not. The median OS in the treated group was extended by 16 months.

- Age has been identified as one of the most important prognostic factors for HCC.13-15 However, studies that compare the prognosis between elderly and non-elderly patients with HCC while adjusting for disease severity and treatment status are lacking. It is important to note that the prognosis of HCC varies depending on the stage, and various treatment methods are available depending on the stage of the disease.11,16,17 Therefore, in this study, the survival outcomes of elderly and non-elderly patients with HCC were compared within each tumor stage and treatment modality. The analysis was adjusted for individual clinical and tumor characteristics using IPTW to account for potential confounding factors.

- In early-stage HCC, elderly patients treated with local ablation therapy (log-rank test, P=0.052) and transarterial therapy (log-rank test, P=0.079) had survival outcomes comparable to those of non-elderly patients. Local ablation is one of recommended treatment methods for early-stage HCC with a longest diameter of ≤3 cm.18 Two previous studies of HCC patients who underwent local ablation therapy also showed a non-inferior survival rate of elderly patients compared to that of non-elderly patients.19,20 In contrast, in early-stage HCC patients treated with surgery, one of the optimal treatment options for early-stage HCC tumors with any longest diameter, the survival outcome of elderly patients was poorer than that of non-elderly patients in the present study (log-rank test, P<0.001). As previous studies have shown comparable outcomes between elderly and non-elderly patients with early-stage HCC treated with surgery, further prospective studies are needed to better understand the factors influencing survival outcomes in this specific population.21,22 Based on the findings of the present study, it is important to carefully select the treatment modality for elderly patients with early-stage HCC, taking into account the individual patient’s clinical and tumor characteristics.

- Transarterial therapy is an effective and representative treatment for intermediate-stage HCC.23 In this study, elderly patients had comparable survival outcomes to non-elderly patients with intermediate-stage HCC treated with transarterial therapy (log-rank test, P=0.104). Few studies have directly compared the outcomes of elderly and non-elderly patients with intermediate-stage HCC treated with transarterial therapy. In a previous study of patients treated with transarterial chemoembolization, patients ≥75 or <75 years of age also had similar OS rates.24 These findings support the need for an active treatment approach such as transarterial therapy in elderly patients with intermediate-stage HCC, as nearly 20% of patients in the elderly group received only best supportive care. Surgery can be considered a treatment option for intermediate-stage HCC, if available. In intermediate-stage HCC patients treated with surgery, the survival outcomes of elderly patients were comparable to those of non-elderly patients (log-rank test, P=0.553). This suggests that with careful patient selection, surgery can be an effective treatment approach for elderly patients at this disease stage who exhibit favorable characteristics. The lack of studies comparing surgical treatment outcomes between elderly and non-elderly patients with intermediate-stage HCC highlights the need for further well-designed studies.

- Finally, an important implication of this study is that elderly and non-elderly patients with advanced-stage HCC can achieve comparable survival outcomes when receiving appropriate treatment. Elderly patients had survival outcomes comparable to those of non-elderly patients when treated with transarterial (log-rank test, P=0.066) or systemic (logrank test, P=0.079) therapy. Systemic therapy is one of the treatment methods that has shown a significant increase in survival rates for patients with advanced HCC.25-27 Furthermore, various treatment methods including transarterial and external beam radiation therapy are also performed in the management of advanced-stage HCC.28 In this study, 40% of elderly patients with advanced-stage HCC did not receive any treatment. This could be attributed to the preconception that elderly patients may not tolerate the burden of advanced cancer.

- However, based on these findings, active treatment with transarterial or systemic chemotherapy could be applied in elderly patients with advanced-stage HCC, if there are no contraindications for treatment.

- Moreover, new systemic chemotherapies, including atezolizumab with bevacizumab, which have shown higher efficacy and safety, have recently been adopted as the first-line treatment for advanced-stage HCC.29 A previous study showed that the effect of atezolizumab with bevacizumab treatment for elderly patients was not inferior to that of non-elderly patients.30 With recent advances in immunotherapy in advanced-stage HCC, a significant number of previously untreated elderly patients will now be eligible for treatment.29 Transarterial radioembolization can be given to patients with a large tumor burden who are difficult to treat with transarterial chemoembolization. It has also been reported to have a lower incidence of adverse effects, making it a potentially suitable option for elderly HCC patients.31-33

- Our study had several limitations. First, because the study sample was derived from the KCCR, the selection of patients from this registry could have introduced an inherent selection bias. Although IPTW and PSM were used to correct for selection bias, residual confounding factors may still exist. Second, because of the retrospective design of this study, which relied on data collected from medical records, an information bias may have existed. Third, this study focused only on patients with HCC in Korea, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations or healthcare systems. Factors such as regional variations in healthcare practices and treatment guidelines could influence these results. Fourth, HCC is a complex disease requiring high-quality hospital facilities and multidisciplinary collaboration for treatment. Since our data were randomly collected from hospitals all over the country, the treatment capacity and circumstances of each institution, which can be important factors in treatment selection, have not been well examined. Fifth, caution should be exercised in interpretation as definitions of the elderly vary across studies. In addition, there has been a continuous argument for a change in the age defining the elderly in South Korea. Finally, liver cirrhosis was not used as a variable in this study because the dataset lacked information about the presence of liver cirrhosis.

- In conclusion, elderly patients with HCC can be effectively treated if the selection of an appropriate treatment is aligned with their clinical and tumor characteristics. However, it is crucial to make treatment decisions judiciously, considering the patient's overall health condition and individual circumstances. Careful evaluation and personalized approaches are necessary to optimize treatment outcomes in elderly patients with HCC.

DISCUSSION

-

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

-

Ethics Statement

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Ewha Womans University Hospital waived the need for IRB approval and written informed consent (IRB No. 2023-02-028) because the KPLCR data were collected anonymously as part of the KCCR in accordance with the cancer control act.

-

Funding Statement

None.

-

Data Availability

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

Author Contribution

Conceptualization: SL

Data curation: HAL, SL, HLL, JES, DHL, SH, JHS, BHK, JYC, HR, DYK

Formal analysis: HAL

Funding acquisition: HAL

Investigation: HAL, DYK

Methodology: HAL, DYK

Project administration: HAL

Supervision: DYK

Validation: HAL, DYK

Visualization: HAL, DYK

Writing–original draft: HAL, SL, HLL, JES, DHL, SH, JHS, BHK, JYC, HR, DYK

Writing–review & editing: HAL, SL, DYK

Approved the final manucript: all authors

Article information

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

| Variable | Elderly (n=5,829) | Non-elderly (n=9,357) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | ||||

| Age (year) | 72.0 (68.0-77.0) | 54.0 (49.0-59.0) | <0.001 | |

| Male | 4,155 (71.3) | 7,879 (84.2) | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes, misssing=191 | 2,003 (34.8) | 1,934 (21.0) | <0.001 | |

| Hypertension, missing=205 | 3,016 (52.4) | 2,199 (23.8) | <0.001 | |

| Smoking, missing=200 | 1,914 (33.2) | 4,824 (52.3) | <0.001 | |

| Etiology | <0.001 | |||

| Hepatitis B virus* | 1,971 (33.8) | 7,094 (75.8) | ||

| Hepatitis C virus | 1,031 (17.7) | 535 (5.7) | ||

| Alcohol | 1,056 (18.1) | 811 (8.7) | ||

| Others | 1,771 (30.4) | 97 (9.8) | ||

| Laboratory variables | ||||

| Serum albumin, missing=392 (g/dL) | 3.7 (3.2-4.1) | 3.9 (3.3-4.3) | <0.001 | |

| Total bilirubin, missing=374 (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) | 1.0 (0.7-1.6) | <0.001 | |

| INR, missing=642 | 1.10 (1.03-1.20) | 1.11 (1.04-1.22) | 0.002 | |

| Alanine aminotransferase, missing=359 (IU/L) | 31 (20-52) | 39 (25-62) | <0.001 | |

| Platelet count, missing=488 (×109/L) | 146 (100-206) | 143 (98-197) | <0.001 | |

| Creatinine, missing=458 (mg/dL) | 0.90 (0.75-1.10) | 0.86 (0.71-1.00) | <0.001 | |

| MELD score, missing=1,109 | 9.0 (7.0-11.0) | 8.0 (7.0-11.0) | 0.015 | |

| Child-Pugh class, missing=767 | <0.001 | |||

| A | 4,025 (72.5) | 6,480 (72.3) | ||

| B | 1,299 (23.4) | 1,968 (22.2) | ||

| C | 229 (4.1) | 490 (5.5) | ||

| Tumor variables | ||||

| Alpha-fetoprotein, missing=1,302 (ng/mL) | 22.1 (5.0-340.0) | 47.8 (6.9-957.0) | <0.001 | |

| Tumor number, missing=72 | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | 3,598 (62.0) | 5,677 (61.0) | ||

| 2 | 877 (15.2) | 1,219 (13.2) | ||

| 3 | 251 (4.3) | 337 (3.6) | ||

| 4 | 95 (1.6) | 120 (1.3) | ||

| ≥5 | 984 (16.9) | 1,956 (21.0) | ||

| Maximal tumor diameter, missing=1,670 (cm) | 3.5 (2.0-6.4) | 3.0 (1.9-6.0) | <0.001 | |

| Modified UICC stage, missing=115 | <0.001 | |||

| Stage I | 777 (13.4) | 1,496 (16.1) | ||

| Stage II | 2,314 (40.0) | 3,328 (35.9) | ||

| Stage III | 1,620 (28.0) | 2,232 (24.0) | ||

| Stage IV-A | 573 (9.9) | 1,215 (13.1) | ||

| Stage IV-B | 504 (8.7) | 1,012 (10.9) | ||

| BCLC stage, missing=531 | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 582 (10.0) | 1,096 (11.7) | ||

| A | 2,283 (39.2) | 3,318 (35.5) | ||

| B | 829 (14.2) | 1,009 (10.8) | ||

| C | 908 (15.6) | 1,797 (19.2) | ||

| D | 934 (16.0) | 1,606 (17.2) | ||

Values are presented as median (interquartile range) or number (%).

INR, international normalized ratio; MELD, model for end stage liver disease; UICC, Union for International Cancer Control; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer.

* Patients co-infected with hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus (n=178) were also included.

- 1. Statistics Korea. Annual report on the causes of death statistics 2019 [Internet]. Daejeon (KR): Statistics Korea; [cited 2021 Feb 1]. Available from: https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10301060100&bid=218&act=view&list_no=385219&tag=&nPage=1&ref_bid=

- 2. National Cancer Center. Annual report of cancer statistics in Korea in 2018 [Internet]. Goyang (KR): National Cancer Center; [cited 2021 Feb 1]. Available from: https://ncc.re.kr/cancerStatsView.ncc?bbsnum=558&searchKey=total&searchValue=&pageNum=1

- 3. Kim DY, Han KH. Epidemiology and surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer 2012;1:2−14.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 4. Cho Y, Kim BH, Park JW. Overview of Asian clinical practice guidelines for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an Asian perspective comparison. Clin Mol Hepatol 2023;29:252−262.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 5. Statistics Korea. Population projections and summary indicators (Korea) [Internet]. Daejeon (KR): Statistics Korea; [cited 2023 May 1]. Available from: https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1BPA002&conn_path=I2&language=en

- 6. Maucort-Boulch D, de Martel C, Franceschi S, Plummer M. Fraction and incidence of liver cancer attributable to hepatitis B and C viruses worldwide. Int J Cancer 2018;142:2471−2477.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 7. Chon YE, Park SY, Hong HP, Son D, Lee J, Yoon E, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence is decreasing in Korea but increasing in the very elderly. Clin Mol Hepatol 2023;29:120−134.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 8. Korean Association for the Study of the Liver (KASL). KASL clinical practice guidelines for management of chronic hepatitis B. Clin Mol Hepatol 2022;28:276−331.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 9. Macias RIR, Monte MJ, Serrano MA, González-Santiago JM, Martín-Arribas I, Simão AL, et al. Impact of aging on primary liver cancer: epidemiology, pathogenesis and therapeutics. Aging (Albany NY) 2021;13:23416−23434.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 10. Seo JH, Kim DH, Cho E, Jun CH, Park SY, Cho SB, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of extreme elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in South Korea. In Vivo 2019;33:145−154.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 11. Korean Liver Cancer Association (KLCA), National Cancer Center (NCC) Korea. 2022 KLCA-NCC Korea practice guidelines for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Mol Hepatol 2022;28:583−705.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 12. Tabrizian P, Saberi B, Holzner ML, Rocha C, Kyung Jung Y, Myers B, et al. Outcomes of transplantation for HBV- vs. HCV-related HCC: impact of DAA HCV therapy in a national analysis of >20,000 patients. HPB (Oxford) 2022;24:1082−1090.ArticlePubMed

- 13. Lok AS, Seeff LB, Morgan TR, di Bisceglie AM, Sterling RK, Curto TM, et al. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma and associated risk factors in hepatitis C-related advanced liver disease. Gastroenterology 2009;136:138−148.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Sohn W, Paik YH, Cho JY, Lim HY, Ahn JM, Sinn DH, et al. Sorafenib therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma with extrahepatic spread: treatment outcome and prognostic factors. J Hepatol 2015;62:1112−1121.ArticlePubMed

- 15. Nguyen VT, Amin J, Law MG, Dore GJ. Predictors and survival in hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma in New South Wales, Australia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;24:436−442.ArticlePubMed

- 16. Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, Zhu AX, Finn RS, Abecassis MM, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018;68:723−750.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 17. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2018;69:182−236.ArticlePubMed

- 18. Shiina S, Tateishi R, Arano T, Uchino K, Enooku K, Nakagawa H, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: 10-year outcome and prognostic factors. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:569−577. quiz 578.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 19. Takahashi H, Mizuta T, Kawazoe S, Eguchi Y, Kawaguchi Y, Otuka T, et al. Efficacy and safety of radiofrequency ablation for elderly hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Hepatol Res 2010;40:997−1005.ArticlePubMed

- 20. Hiraoka A, Michitaka K, Horiike N, Hidaka S, Uehara T, Ichikawa S, et al. Radiofrequency ablation therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;25:403−407.ArticlePubMed

- 21. Kishida N, Hibi T, Itano O, Okabayashi K, Shinoda M, Kitago M, et al. Validation of hepatectomy for elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:3094−3101.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 22. Wu FH, Shen CH, Luo SC, Hwang JI, Chao WS, Yeh HZ, et al. Liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in oldest old patients. World J Surg Oncol 2019;17:1. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 23. Llovet JM, Real MI, Montaña X, Planas R, Coll S, Aponte J, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002;359:1734−1739.ArticlePubMed

- 24. Nishikawa H, Kita R, Kimura T, Ohara Y, Takeda H, Sakamoto A, et al. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for intermediatestage hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical outcome and safety in elderly patients. J Cancer 2014;5:590−597.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 25. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2008;359:378−390.ArticlePubMed

- 26. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 noninferiority trial. Lancet 2018;391:1163−1173.ArticlePubMed

- 27. Kim Y, Lee JS, Lee HW, Kim BK, Park JY, Kim DY, et al. Sorafenib versus nivolumab after lenvatinib treatment failure in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023;35:191−197.ArticlePubMed

- 28. Yoon SM, Lim YS, Won HJ, Kim JH, Kim KM, Lee HC, et al. Radiotherapy plus transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma invading the portal vein: long-term patient outcomes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;82:2004−2011.ArticlePubMed

- 29. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1894−1905.ArticlePubMed

- 30. Vithayathil M, D'Alessio A, Fulgenzi CAM, Nishida N, Schönlein M, von Felden J, et al. Impact of older age in patients receiving atezolizumab and bevacizumab for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int 2022;42:2538−2547.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 31. Dhondt E, Lambert B, Hermie L, Huyck L, Vanlangenhove P, Geerts A, et al. 90Y radioembolization versus drug-eluting bead chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: results from the TRACE phase II randomized controlled trial. Radiology 2022;303:699−710.ArticlePubMed

- 32. Cho YY, Lee M, Kim HC, Chung JW, Kim YH, Gwak GY, et al. Radioembolization is a safe and effective treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein thrombosis: a propensity score analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0154986.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 33. Golfieri R, Bilbao JI, Carpanese L, Cianni R, Gasparini D, Ezziddin S, et al. Comparison of the survival and tolerability of radioembolization in elderly vs. younger patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2013;59:753−761.ArticlePubMed

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

- Efficacy and Safety of Surgical Resection in Elderly Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Jin-Soo Lee, Dong Ah Park, Seungeun Ryoo, Jungeun Park, Gi Hong Choi, Jeong-Ju Yoo

Gut and Liver.2024; 18(4): 695. CrossRef - Achieving Sufficient Therapeutic Outcomes of Surgery in Elderly Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients through Appropriate Selection

Han Ah Lee

Gut and Liver.2024; 18(4): 556. CrossRef

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Download Citation

Download Citation

- Download Citation

- Close

- Related articles

-

- Changing etiology and epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: Asia and worldwide

- Radiofrequency for hepatocellular carcinoma larger than 3 cm: potential for applications in daily practice

- Intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: refining substaging or shifting paradigm?

- Comparison of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and lenvatinib for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis

- Treatment options for solitary hepatocellular carcinoma ≤5 cm: surgery vs. ablation: a multicenter retrospective study

E-submission

E-submission THE KOREAN LIVER CANCER ASSOCIATION

THE KOREAN LIVER CANCER ASSOCIATION

Follow JLC on Twitter

Follow JLC on Twitter